“I err, therefore I am.” ~ Saint Augustine.

On every path there comes a crossroads. At every crossroads there is a choice. In Zoroastrianism, the religion of Zarathustra, souls must cross a bridge after they die. The blessed will cross over into Garo Demana– the House of Song, while the damned head for Drujo Demana – the House of the Lie. And so it is in life.

Governing the precept that life is a series of rebirths, filled with tiny deaths in between, it stands to reason that within each transition from death to rebirth there is a bridge, a crossroads, at which our souls must make a decision: get busy living or get busy dying.

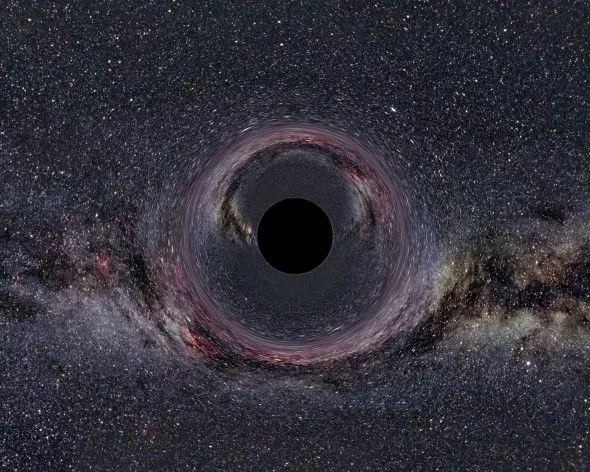

Do we challenge ourselves in Garo Demana (the House of Song) or do we head for the easy lies of Drujo Demana (the House of Lies)? And, of course, do we walk the path toward The Theater of the Absurd, where we are free to act out the adventure of our life in full creative abandon, or do we follow the path toward The Existential Blackhole where all adventures end? The choice seems to be easy. But living is difficult. It’s dying that’s easy.

The Existential Blackhole, like Drujo Demana, is a meta-symbol representing meaninglessness and nihilism. It is a maelstrom of psycho-spiritual emptiness, a void of pure oblivion. It is a metaphor for the end of a life that somehow keeps on living.

It represents the end to self-actualized living and an end to the examined life. Within the Existential Blackhole everything has become extreme; where instead of living freely, one begins to live in chains, bound to, and limited by, the conjectures of other men.

Two powerful archetypes emerge from this realm: the Priest (the pietistic ego) and the Nihilist (the irreverent ego). They are each wrought from the same mold: an extreme misperception of reality. One extremely defends, while the other extremely renounces.

The Priest gets sucked into the Blackhole because he rejects his humanity for his spirit. The Nihilist gets sucked into the Blackhole because he rejects his spirit for his humanity. Either way, there is unnecessary suffering and extreme close-mindedness.

One might ask how this can happen. How can people so easily shun the rest of reality, and all that it has to offer, for a tiny sliver of spoon-fed misconception? The answer is that we are insecure, fallible animals who believe that we are secure, infallible gods. It seems our hypocrisy knows no bounds. And when it comes to the concept of death and the afterlife, we are hypocrites par excellence.

“To agree that we can be wrong about ourselves,” writes Kathryn Schulz “we must accept the perplexing proposition that there is a gap between what is being represented (our mind) and what is doing the representing (also our mind).”

This paradox of representation strikes at the heart of the human condition. The fact that we are inherently fallible creatures should be the first red flag that pops up when we feel certain about our beliefs.

Colin Martindale’s concept of sub-selves and the modular mind shows us that we actually have a number of executive sub-selves that all occasionally manage our perception of reality. The hypocrisy that arises from such a condition, torn between so many worlds, is unavoidable. We might as well embrace it, and even somehow get better at it. The philosophical principle of fallibilism is what we do with the space in between worlds.

That is to say, with the representation and the representing, what Slavoj Žižek referred to as the Parallax Gap. This is the space that both the Priest and the Nihilist fear. It’s the space just out of reach of our comfort zone. It’s the crack between the shattering of our mental paradigms.

If we fill this space with flexible transparency, with fallibilism, we leave ourselves open-minded enough to correct for errors in our reasoning and thus allow the potential for new knowledge. A person with a fallibilistic disposition realizes that wisdom begins first with not ignoring our ignorance, and second with becoming aware of our fallibility.

It seems absurd to embrace fallibility in this way. But the deeper into the absurd we go, the higher we are launched into the sacred. How far we walk into the sacred shrinks or expands in proportion to the extent that we are able to stretch ourselves between meaningless absurdity and higher spirituality.

Consider absurdity as a sacred screwdriver loosening our self-serious screws so that we can breathe and, finally, laugh. “This is the wisdom behind absurdity.” Bradford Keeney writes, “It teaches the value of the displaced and disqualified other side. It belittles the revered, and celebrates any and all irrational means of bringing opposites back in line with one another.”

But before we can recognize the wisdom behind absurdity, we must first discover the path toward the Theater of the Absurd, the bridge to Garo Demana, where the ego’s pride in itself is debunked, not masochistically, but in the spirit of cosmic humor. A cosmic humor that is nothing less than divine self-awareness. It is the delighted recognition of one’s absurdity and a loving cynicism toward one’s pretenses.

Recognizing that we all suffer from self-serving bias, confirmation bias and cognitive dissonance is a powerful step toward achieving the cognitive humility discovered on this path. After all, bias is the reason why Goethe advised us: “one must ask children and birds how cherries and strawberries taste.”

Image Source: